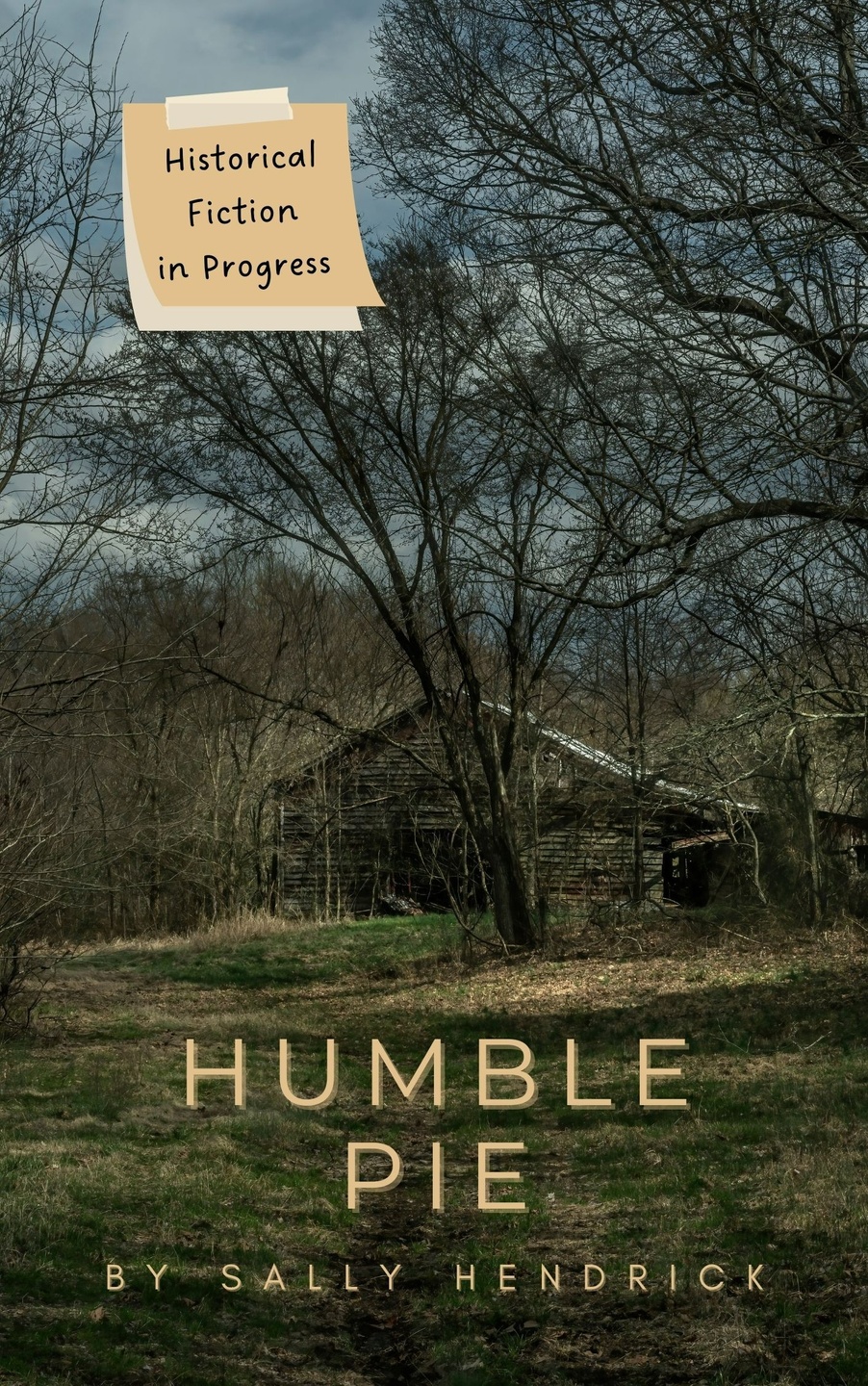

The editor's father, Kimbrough Dunlap, wrote this story in the late 1980's or early 1990's. She has rediscovered his research and has been going through it to help her write her historical fiction novel, Humble Pie.

by Kimbrough Dunlap

Humboldt is a rural west Tennessee town located on the crossing of two major railroads once noted for shipping strawberries and vegetables grown in the richest soil found anywhere in the state, while Coxville is a tiny farming community a few miles west of the railhead. Tiny is an accurately descriptive word for Coxville. It has a store and a few churches, but even since pioneer days, it has never been big enough to warrant a post office. That is small by west Tennessee standards, where post offices still exist with populations not much larger than number in the zip code. Coxville residents are farmers and descendants of farmers that rank with the best found anywhere in Tennessee. They are proud people that have passed their land down from generation to generation since settlement in the 1820s. In 1929 an incident occurred at Coxville that has long been forgotten, and this is where our story begins.

Johnny James and his lovely wife, Minnie, ran a successful farming operation at Coxville in earlier days. Johnny was a squire and a respected man, and Minnie was a popular lady active in her church. Both were descendants of those early settlers. In fact Minnie was a Cox before she married; a family so numerous the community was named for them.

Several black families lived on the James place to help work the land, as was typical in that era, and business was usual that spring with everyone busy picking strawberries, planting cotton, cutting cabbage, you name it on a labor intensive farm, when 19 year old Joe Boxley showed up at the James house supposedly to buy some stamps. Minnie was home alone that morning, but Joe’s presence was no cause for alarm. He was raised on the place, and Minnie trusted him completely. Joe had been around the house many times.

This day, May 28, things were about to be different. Joe allegedly assaulted Mrs. James and left her unconscious, where she was found two hours later by Joe’s stepmother. When Joe was discovered missing, the sheriffs of both Crockett and Gibson Counties were notified, and word spread that Joe Boxley was suspected of the crime. Before the day ended, Joe was apprehended near Eaton in Gibson County and taken to the Trenton jail by Fred Lawler, Albert Givens and Clay Hall. About dark a large crowd mostly from Crockett County and Humboldt, estimated between 100 and 200 in number, began to congregate near the jail.

The men made an attempt to take Joe from the jail by beating down the outer door, but they were unsuccessful, when they could not get through the inner tier of cells. The crowd quieted down for awhile, but when a group came from Crockett County with word that Mrs. James had regained consciousness and identified Joe as the assailant, the mob made a renewed effort to gain entry and was making substantial progress, when Sheriff Guy Bradshaw made an appeal that worked.

He told a small group of leaders that he was running for reelection, and since the crime had occurred in Crockett County, he wanted their permission to allow him to turn the prisoner over to the Crockett County sheriff and let him off the hook. Sheriff Bradshaw bought some time with his appeal, and the crowd allowed him to leave with the prisoner, with the understanding that Joe would be taken to the Crockett County jail.

Out the back and into the night the sheriff went with his prisoner, but the destination was the Dyer County jail in Dyersburg. The Dyer County sheriff wanted no part of the problem, and Sheriff Bradshaw had no choice but to transport Boxley to Alamo and turn him over to Crockett County sheriff, Carl Emison.

When Sheriff Bradshaw deposited the prisoner in Alamo and quickly departed for Gibson County, his problems ended, while Sheriff Emison’s problems were just beginning. The crowd was bigger than ever, and it was whipped into a frenzy. When a group entered the outer office of the jail and demanded the prisoner, Sheriff Emison informed them the keys were missing, and the cell holding Boxley could not be opened. The group made a search for the keys that were easily found. A newspaper article reported the keys were discovered under the cushions of a lounge in the residence section of the jail. Another source said the keys were under a rug in the center of the room, where they formed a suspicious looking hump. Take your pick; Joe Boxley was on the front lawn of the jail in a twinkling of the eye.

Sheriff Emison was helpless facing such a large crowd late in the night. Boxley was identified as the guilty person, and he confessed to the crime according to the newspaper report attached (There was no attachment found.). Defending Boxley would likely have been unsuccessful, while putting the sheriff’s life in jeopardy. Oh, we know, the movies often depicted the white-hatted sheriff defending a doubtfully guilty prisoner, and the hero always came out on top. Well, this wasn’t the movies, and Sheriff Emison wasn’t likely to come out on top. What the sheriff did do was buy the prisoner a little more time, where something might occur to change things. The crowd was about to hang Boxley on the lawn in front of the jail, when Emison successfully appealed to the crowd to leave and do their deed elsewhere.

The mob left with the car carrying the prisoner leading a caravan of automobiles east toward the Coxville community, where the crime had been committed. When they reached the Cypress Creek area a few miles short of their intended destination, a sturdy elm tree was spied beside the road, and the caravan stopped. Dawn would soon be approaching, and it was time to get on with the business at hand. The two sheriffs had almost succeeded with their stalling tactics, so that daylight might change the mood of the crowd. It didn’t work, and Joe Boxley was hanged beside the road in the early morning hour May 29, 1929.

A picture of Boxley taken that morning before he was cut down, showed his fists clinched tight, but his hands were not tied, and there were no marks on his body to indicate that he had been tortured. The Humboldt Courier Chronicle reported the following day that a card was attached to the body, which said not to remove the body until 4 o’clock in the afternoon. The sign was actually a little more descriptive than reported, but the meaning was the same.

Word spread fast across both counties, and traffic out to where the body was left hanging was bumper to bumper all morning long, before and after the body was cut down. Many pictures were taken, and the Shackleford Drug Store in Trenton later had pictures made into postcards that sold for 50 cents apiece. A newspaper report said the boy was cut down by authorities sometime that morning, which was probably correct. However, a rumor circulated that the body was left hanging until a black undertaker arrived and took the body down. In so doing the body bounced against the wagon and fell to the ground, and the undertaker believing this to be an evil omen, quickly departed with the body left lying in the dirt under the tree. Regardless of how it happened, the body was turned over to the family after an inquest, and Joe was buried at the Porter’s Grove Church cemetery a few miles down the road. While there may have been a temporary marker placed at the grave site at that time, there is no marker today, and Joe lies in an unmarked grave.

The tree eventually died, and the limbs began to fall off over time. The last limb to fall from the trunk was the one that supported Joe’s body the night he was hanged. The entire trunk disappeared completely years later during a construction project on the road.

Carl Emison was a popular sheriff elected to three terms in Crockett County. People knew him wherever he went, and he knew them and collected an overwhelming number of votes each election. Yet, strangely he was unable to identify a single man in the mob that took Joe Boxley from his jail that night. As the years passed by, the barber that tied the knot died, and the name of the man that slipped the noose around Boxley’s neck became hazy. Those that hoisted the body and secured the rope around the tree are all gone now, and the last lynching in Tennessee slipped into history.

Included in Mr. Dunlap's research were two pictures of Joe Boxley hanging from the elm tree. Out of respect for the family, we've decided not to publish them.